Friday, 24 December 2021

I Bloody Love Big Pictures

Thursday, 17 September 2020

"Gruff voices come from inside" (A Nod to John Blanche)

Thirty-seven years after the publication of Steve Jackson's Sorcery! the townspeople of Kristatanti still wear their hair high on their heads. John Blanche's illustrations are nothing like the meticulously researched environments you'll find in Skyrim or other first-person Fantasy walking simulators, they're actual folk art, immersing you in not a tangible landscape but an eccentrically embellished personal mythology, which is probably, really, what you want to be immersed in when you fantasy role play. Here, for example, is the guard who sees you off on your adventure:

Now you'd never see that in a video game. There would be too many questions. And no answers because there's no reason for any of this, other than Blanche's joy in making stuff up. They say a camel is a horse designed by a committee, but actually it looks far more like the pet project of someone who worked on the committee that brought out the horse. And pet projects are the substance of fantasy. We associate the genre with mythology, and we're right to, but mythologies are the product of a people, not a hive. Just bunch of people. There's no way to synthesise their differing accounts - mythology is not synthetic - nor any way of extrapolating what actually happened. Someone simply made something up and that happened lots of times, and I think Blanche's work expresses those instances perfectly.

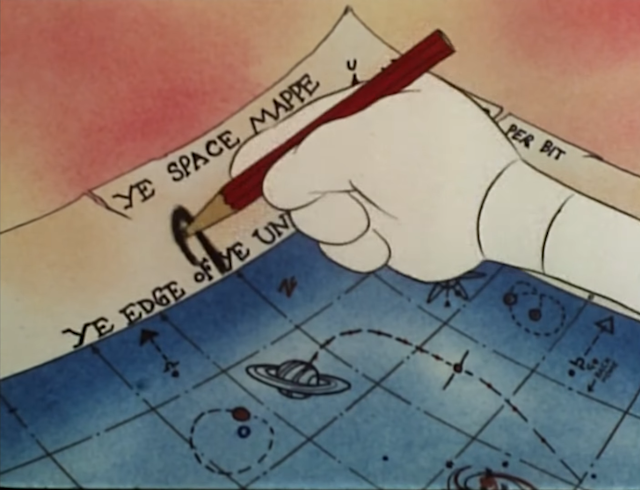

I mean, what's this? Doesn't matter. You encountered it. Or this is how you remember it. I think I enjoyed reading, or playing, The Shamutanti Hills this week even more than I had as a child. Video games in the interim had probably conditioned me a little better for all the keeping track one has to do, and I bothered learning the spells this time too, which came in very handy when I lost my sword halfway through the book. I also took time to make a map, something I'd always written off as a chore before, but it turns out it's a creative act, part of the game: you can draw a small crow where you saw a crow for example, or rolling hills, or heads on spikes when you encounter heads on spikes, a classic shorthand for the outskirts of sub-human savagery despite heads on spikes marking the boundaries of the City of London well into the seventeenth century. Talk about projection.

Thursday, 27 August 2020

Ships, Sea and the Snark

A whatsapp map created for refugees,

presented by Professor Marie Gillespie,

Monday, 6 April 2020

Invisiblish Cities

I wrote before, here, about my ambivalent relationship with maps of non-existent worlds at the beginning of books, but non-maps of non-existent worlds compliment fantasy's undependability far better, and so are fine... Once, last century, when I was allowed to be a film critic for the university paper, I watched Peter Greenaway give an interview in which he said film was the perfect medium for him because he was interested in text and images, and I remember thinking, maybe he should be working in comics instead, because film isn't just words and pictures, it's also time, and his films are quite boring. But I hadn't yet grown to appreciate drifiting in and out of a work, nor had I yet seen his early funny stuff.

"I am the watchman! How do you do? What is the matter?"

Sunday, 12 January 2020

Benchless in Baatu (Jenny Nicholson does some digging)

Here's animator Ward Kimball and his boss larking around at the Chicago Railroad Fair in 1948 (and here's the source). This delightful photograph pops up in the video below, another great piece to camera from Jenny Nicholson and the subject of today's post (I blogged about her visit to Pandora here). If you've absolutely no interest in Disneyland, then move on, dear reader, but if, like me, you think it might be the most impressive work of art of the twentieth century, BOY does Nicholson deliver! "Star Wars Land: An Excruciatingly in-Depth Prequel" is an almost literal dissection of the place. Here's a map:

It is a map I grew up with – hung by the front door where we kept our wellies – of Disneyland from 1976. Dad was a huge fan. When I finally visited the park in the nineties – although I didn't take it in at the time – the area depicted just to the left of Fantasyland was unrecognisable. I'll enlarge it a bit:

Those tracks are a ride called "Nature's Wonderland". Nicholson's video is full of footage showing it was more than just a mine train ride (although "Walt Loved Trains", and Nicholson makes a great argument for the whole of Disneyland being one huge train set). The place was actually crammed with many modes of transport...

Importantly they served not only as "conveyances" but a "futuristic mode of ornamentation." To quote Nicholson: "they are not just rides for the people who are on them, they are also symbiotically enhancing the experience for everyone in their sightline."

Friday, 10 January 2020

Shadow-Unboxing (or: Why I'm totally fine with the map of Earthsea)

"To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment.Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven."Chang Tzu

This is the ball-ache that greets any reader opening Ursula K. Le Guin's "A Wizard of Earthsea". For much of the book, it appears to be an example of exactly the kind of map-at-the-beginning-of-a-book I talked about dreading in yesterday's post – the kind you're meant to constantly refer back to while following the hero's journey, an impediment to reading, crammed with unnecessary detail, imprisoning upon the page a world which the act of reading is supposed to liberate. But Le Guin's brilliant, and clearly knew what she was doing, because SPOILERS! the book's climax takes place off the map. It's only beyond the edge of the world that Ged can name his shadow, and – like Dangermouse in "Custard" – let reality catch up with him. The map isn't here to show us where the hero went, but to show us, physically in fact, what he had to escape. It's an excellent way of depicting magic. I'm guessing. I'm very glad I re-read it.

"Every story must make its own rules. And obey them." I was inspired to read more Le Guin because of an excellent documentary no longer available on iplayer but still viewable here. And I haven't read any of the other Earthsea books yet. Nor worked out what the point of the map at the beginning of "The Dispossessed" was either so, you know, maybe I'm wrong and she just liked maps.

Thursday, 9 January 2020

Why Not Build A World? (Enjoying the Unvisitable)

I'm very sympathetic to the idea that all the best fiction has a map at

the front, but I'm not a complete convert. Different maps serve

different puposes: the map in The Hobbit is a call to adventure, while the maps of the Hundred Acre Wood or Moominvalley

are more like welcoming gifts. Both types are pretty scant on detail, and

both are types I like: maps you don't have to constantly refer to. It's

not just laziness that makes me favour these maps, it's that they

make no serious attempt to pretend – as some fantasies do – that

imagined lands can be depicted objectively.

I'm very sympathetic to the idea that all the best fiction has a map at

the front, but I'm not a complete convert. Different maps serve

different puposes: the map in The Hobbit is a call to adventure, while the maps of the Hundred Acre Wood or Moominvalley

are more like welcoming gifts. Both types are pretty scant on detail, and

both are types I like: maps you don't have to constantly refer to. It's

not just laziness that makes me favour these maps, it's that they

make no serious attempt to pretend – as some fantasies do – that

imagined lands can be depicted objectively."Like all books, Viriconuim is just some words. There is no place, no society, no dependable furniture to 'make real'. You can't read it for that stuff, so you have to read it for everything else."I was delighted to see Harrison's name pop up. I've always loved "In Viriconium" – there's a detectable Viriconian influence here for example. Like Bastian's Fantasia in "The Neverending Story" the city is unmappable. In my spare periods at school, I used to walk along the then undeveloped South Bank in the shadow of Bankside Power Station (now Tate Britain) looking for places Viriconium might be, scouting liminal locations. And any reader in any other city could do the same.