Nearly 20 years after its first London outing, Simon Kane is reviving Jonah Non Grata, a solo show that merges absurdism, hymns, and a heavy dose of holy confusion. This surreal, comic exploration of power, extremism, and meaning feels sharper than ever in 2025. We caught up with Simon Kane to unpack his return to the Fringe, the joy of “failed magic,” and the art of staying baffling.

You’re reviving Jonah Non Grata nearly 20 years after its first London outing. What made you return to this gloriously strange beast now?

It’s tempting to say something glib about the absurdity of religious conflict, but I think what’s most important about the show right now is how baffling it is. Good art can get us talking, but really good art can get us to shut up. There’s a lot to be said for reaching out to people through a piece that defies demographics by not making sense to anyone. But the real answer is, I missed it, and I could now afford it.

The show mixes hymns, failed magic tricks, and audience interaction. How do you choreograph chaos without completely surrendering to it?

Entropy keeps the chaos in balance, and a lot of this show errs on the side of grinding to a halt. I added a line this year: “Waiting is also a way of joining in.” So it’s not really chaos. Also, all that’s just in the first third. There are proper scenes and everything later on. It’s like tapas.

You call it a “clownish mystery play.” What does that mean to you – and how does that genre-bending shape audience expectations?

I guess that description is meant to suggest a shabby, human-scale stab at the unknowable. Mystery Plays were the earliest plays in (sort of) English – Bible stories played with a realism bordering upon absurdity by local Guilds. I think it’s helpful to base an absurd work on a simple story most people already know. Even if they don’t know that’s what they’re watching, something will chime.

This is a solo show, but it feels full of shifting characters and perspectives. How do you maintain that energy and dynamism alone on stage?

I’ve realised a lot of the inspiration for this show came from simply asking, what do I want to do onstage. I know why my character does what they’re doing, and I don’t mind if the audience doesn’t, because as long as I know, it will still be watchable, maybe even more so than if the audience knew. Their curiosity provides the dynamism. That, and the songs help.

Power, extremism, meaning – your themes hit harder in 2025. How have the world’s changes affected your interpretation of Jonah’s story?

Jonah’s look of double denim, bare chin and big sideburns was originally based on me very much not wanting to look like anyone’s idea of a terrorist, and that certainly changed, but I don’t mourn the passing of that prejudice. I was a little worried some themes might seem too glib now, but I’d forgotten how abstract the piece is. Although a personal sequel to Shunt’s Gunpowder-plot-inspired, coincidentally 9/11-adjacent show Dance Bear Dance, it’s not really about terrorism at all. It’s about an abandoned protagonist’s power fantasy, and love is as much a part of that fantasy as obliteration.

What’s it like re-entering the belly of the beast – literally and figuratively – after so long away from this material?

I’m incredibly excited. The body has modes, I guess. I’ve just been writing television sketches for Mitchell and Webb again, and it turns out the last time I did that was in 2010, but it doesn’t feel like that. Jonah was never off the table, let’s put it like that. If you want someone to see your work, and your work’s a show, you have to do it again.

You’ve worked with experimental companies like Shunt. What role does ‘poor theatre’ or lo-fi absurdity play in your creative process today?

Ultimately, all immersive work has to do is acknowledge your shared environment, and that’s cheap as chips. Working with Shunt was a dream come true, inasmuch I’d always wanted to make work that was funny in a way I hadn’t seen things be funny before – because that’s what I grew up loving – and Shunt were deadpan and pithy and wildly creative and wildly ambitious, but of course they ended up with a real budget, and every -fi going, which they used brilliantly. Maybe just as strong then is an earlier influence: a writer, performer, and director a few Shunt artists and I had worked with at Cambridge called Jeremy Hardingham. We did a show with him in 1997 around the streets of Edinburgh called “Incarnate”, based on the Gospels, and interspersed with interviews with Drew Barrymore and sound bites from Reservoir Dogs, which maybe makes it sound awful, but Jeremy’s script was brilliant and beguiling, and his no-budget, Pop Absurdist pilfering was a huge influence on Jonah. He never liked the title The Empty Space, because there are no empty spaces – Who plays in an empty space? – but taking everything Peter Brook wrote about “play”, and trying it out with an artist who actually knows how to play… that freedom, that power… making a show up becomes surprisingly easy once you’ve got that under your belt.

How do you want audiences to feel when they leave Jonah Non Grata – confused, comforted, or just covered in metaphorical rice pudding?

Do you know the Monty Python Confuse-A-Cat sketch? Confused only like that cat. Newly mobile. Reset. Maybe even like they want to make their own version. Like they can do anything. I don’t want the venue to hate me though, so no rice pudding. I want people to have had fun, and feel they’ve come through something safely.

You describe Jonah Non Grata as “a clown take on a modern-day mystery play.” Tell us a bit more about this.

The first show I wrote on my own, rather than co-devising with fun people like Shunt who’d actually studied theatre, was a modern-day prequel to Shakespeare’s Othello, because I really wanted to play Iago, and had also just been to Cairo with Sulayman Al-Bassam’s “Al Hamlet Summit”, so any work seemed fair game. For my second play I wanted to go even further back for inspiration, to the old Mediaeval Mystery plays: rough, semi-realist adaptations of old stories from the Bible. Initially, I considered adapting Jesus’ awkward goodbyes on his return from the dead as described in various Gospels, but then I came across Alasdair Gray’s little Canongate introduction to The Book of Jonah, which he described as “a prose comedy” about “an unwilling prophet” who just “wants God to leave him alone”, and realised this should be the next show, and also that it should be – if not a clown show – at least a show where people felt very comfortable laughing at me.

The show originally debuted nearly 20 years ago. Why revive it now - and what’s changed?

In the show? My eyesight’s got worse, so there’s more audience interaction, as I have to ask people to read stuff out to me. Also, I received a very helpful note, after a late-night performance in 2008, to never let my character lose their temper. The technology that was lying around in 2005 is rarer to source now too, and you can’t just light candles onstage. Bits have been added. Bits have drifted off. But the biggest change is that stupid, evil, wrong people are even more of a problem in the world, and making sense doesn’t seem to be enough to diffuse that. So the show’s absurdity maybe seems more of a radical kindness now – a temporary reprieve from having to be right.

There are hymns, bungled magic tricks, a hotel room, and someone who might be on the moon. What’s your method for weaving such a mix into a cohesive narrative?

Bit by bit. I worry that the more I go into my inspirations for the piece, the more I risk closing off how people might enjoy it. It’s intentionally abstract, but the narrative’s there, in The Book of Jonah. I don’t want audiences to think it’s necessary for them to know that to enjoy the show though. Treat it like a concept album, or a cabaret. Music helps. A lot of the show was made to accompany the music I wanted to put into it. It’s practically a musical.

How does audience interaction influence the tone or outcome of the show if at all?

I’ve realised, in many ways, the show is simply about a character trying to work out how to talk to other people. And those other people are, for the most part, the audience. But because the audience is real, and the character is not, and we know that’s the deal when you come to see a show – a bit like Hamlet’s soliloquies – nothing will ultimately be sorted out. So I think probably the outcome won’t be affected at all. But hopefully watching that failure play out will be something, and maybe even itself feel like a connection.

What’s the strangest or most memorable reaction you’ve had from an audience member?

I think it’s my duty to out-weird the audience, and the richness of an interaction is not in its uniqueness or anecdotal worth, but in the simple fact it’s a reaction. In other words, I don’t remember. Honestly, what I find weirdest is just that so many people get it.

What do you hope to take away from Edinburgh Fringe this year?

Apart from all the stuff you’d expect me to want to take away from performing a show at an International Arts Festival – like love and respect and glory and validation and happy memories and job and book offers – I hope to take away with me some idea of what to do next. I’ve never really made anything as a means to an end, and I have the CV to prove it.

Jonah Non Grata will be at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival this August. For tickets and more information, visit:: https://assemblyfestival.com/whats-on/1076-jonah-non-grata

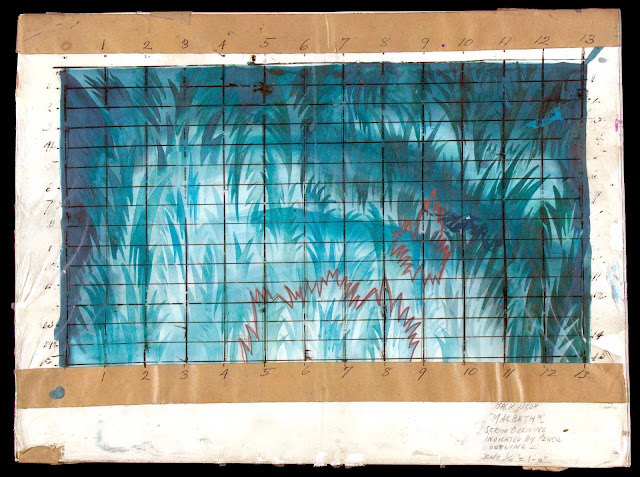

A Jonah-based mural by Alsadair Gray which I have only just this second found out existed.